In Dynamics of Individual Differences course, students acquire in-depth knowledge on how and why personality traits and cognitive abilities change across life and how they interact with each other at different stages in life. Students learn different concepts of change and stability, and how to interpret empirical findings on change. In addition, students learn about the relevance of personality traits and cognitive abilities for various relevant outcomes at different stages in life (e.g., health, job success) and how interventions can improve these outcomes by targeting the psychological constructs. Finally, students learn about the relevance of (changing) personality traits and cognitive abilities for work outcomes. The assignment was to write a short text for the ReMa-IDA Blog "Character Studies". The students choose one of the session (sub-)topics, but are also encouraged to choose a subject on their own.

2020: A year shaped by the coronavirus

Since March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic holds the world in its grasp. To combat the coronavirus, governments worldwide have issued lockdowns and enforced social distancing, i.e. the reduction of personal contacts to a minimum. While these measures appear to be effective in slowing the virus’ spread, there are also concerns that they might fuel a “loneliness epidemic” (Williams, 2020) and it is feared that the lack of social contacts and support could lead to adverse effects on mental well-being. Did these concerns come to pass? And are the effects of reduced social contact the same for everyone?

What is loneliness?

Before we can talk about the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, we first need to make clear what loneliness actually is. Peplau and Perlman (1982) define loneliness as a perceived lack of meaningful social relationships. This perceived lack can occur when either the subjective standards or the actual relationships change. It is important to stress that being alone is not equal to being lonely: Some people feel lonely even if they have many social contacts, if these relationships do not hold up to their standards. On the other hand, people with only a handful of social relationships may not feel lonely at all, as long as these relationships satisfy their needs.

With this definition of loneliness in mind, it stands to reason that a life event such as a pandemic that forces us to refrain from personal contacts leads to increased levels of loneliness. After all, people cannot participate in several social activities the way they might be used to anymore, e.g. partying, team sports, going out, or even just having lunch with others at school or the workplace.

Why is the topic of loneliness so important during a health crisis? Short-term feelings of loneliness are actually quite common and probably have no serious consequences. Chronic loneliness, however, can pose a severe threat for mental and physical health as it is associated with cognitive decline, depression, increased morbidity (e.g. blood pressure) and higher mortality (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010). This makes loneliness as a “side effect” of corona-related measures an issue of great interest from a public health viewpoint.

A country in lockdown: How does loneliness develop?

Of course, it is far too early to make conclusive statements on how loneliness changes in the face of a sudden life event such as this pandemic since the collection and analysis of data is a time-consuming process. But there are already some intriguing early results:

Buecker et al. (2020) conducted a longitudinal study where they (among other things) tracked daily changes in loneliness in a German sample during the first four weeks since pandemic-related measures were implemented in Germany. In general, during the first two weeks there was a slight increase in loneliness, followed by a decrease during the last two weeks. The reason for this might be that individuals had to adapt to their “new life” during the first two weeks, and then were able to compensate the sudden loss of “real life contacts” in the time after. Compared to weekdays, the participants felt less lonely during the weekend. The authors did not comment on why this is the case. However, one possible explanation is that during the weekend there were more activities possible and still allowed (such as spending time outdoors) so that the lack of social contacts was less noticeable.

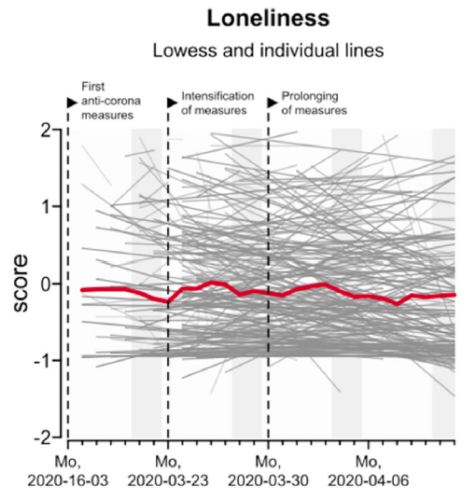

Taking a closer look at the individual development reveals that individuals differ greatly in their trajectories of loneliness. Each gray line in Figure 1 represents how a single person changed overall across the four weeks (some lines are shorter because the individuals dropped out of the study or started earlier). The red line represents the average changes in daily loneliness for the whole sample. It is clear that some people became more lonely, other less lonely, and some even did not change at all.

Figure 1

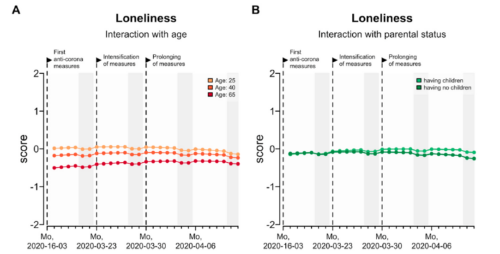

Apparently, not everyone reacts the same to this drastic life event. What are possible reason for these interindividual differences? Buecker et al. (2020) identified two potential risk factors for increased loneliness: age and parental status. In Figure 2A it can be seen that younger individuals reported higher levels of loneliness than older ones at the beginning of the study. On the other hand, the increase in loneliness was stronger for older participants. This might indicate that younger adults can better adapt to social distancing via the use of modern technologies, e.g. video conferencing.

In Figure 2B it becomes apparent that, the longer the lockdown measures were in place, parents reported higher levels of loneliness than adults without children. The reason for this might be that parents had to spend time and attention to supervising their children while schools were closed, which forces them to neglect social relationships outside the family.

Figure 2

To summarise this study: While there were changes in loneliness during the four weeks, these changes differed highly between individuals. It appears that there are certain risk groups, such as parents or older individuals that are vulnerable for loneliness during the pandemic.

What can we do?

How can we deal to reduce feelings of loneliness in times of reduced personal contacts? The NHS has some advice on how to cope with loneliness during the pandemic.

The probably most important option is keeping in contact via digital options such as video conferencing. But you could also aim for meetings “in real life” while still following the rules of social distancing, e.g. by taking a walk in the park while wearing masks.

Another advice is to keep yourself busy by pursuing new skills or explore new hobbies that can be done at home, e.g. listening to audio books, or exercising with online classes. However, keep in mind that you should not try to suppress the feeling of loneliness you might experience! If you do feel lonely, share your feelings and connect to friends – your feelings are valid and you are not “weak” because you feel lonely. Do not hesitate to seek support!

Open questions

As mentioned above, there is still research on the topic of how loneliness changes during lockdowns and social distancing, and how humans differ in their reactions to these pandemic-related measures. Here are some questions that psychologists might be able to answer:

What are risk factors that leave humans vulnerable to feelings of loneliness? As detailed previously, Buecker et al. (2020) already found two possible mechanisms: age and parental status. But maybe there are more, for example more extraverted individuals might be affected more strongly than introverted ones, as they might have a greater need for social contacts. And if we can identify factors that leave people vulnerable to loneliness, can we also develop specific interventions to reduce loneliness for these risk groups?

How does loneliness continue to develop over the whole pandemic? Are humans able to adapt after some time, or does loneliness become worse the longer contact restrictions are in place? And how does culture influence the emergence of loneliness?

Another interesting question is how humans actually define “social contacts”. Can digital meetings (e.g. via videoconferencing) adequately replace meetings “in real life”? If no, what exactly are the components that are missing in digital contacts?

And perhaps there are even positive aspects in this pandemic: If societies learn how to connect while being physically apart from each other, they might be able to become more inclusive to individuals that often were excluded from societal events in the past, such as chronically ill, old or disabled individuals.

Manuel

References

Buecker, S., Horstmann, K. T., Krasko, J., Kritzler, S., Terwiel, S., Kaiser, T., & Luhmann, M. (2020). Changes in daily loneliness for German residents during the first four weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 113541. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113541

Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine : A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8

Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (1982). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy. Wiley.

Williams, J. P. (2020, April 7). How the Coronavirus Pandemic Fuels America’s Loneliness Epidemic. U.S. News. https://www.usnews.com/news/healthiest-communities/articles/2020-04-07/coronavirus-pandemic-fuels-americas-loneliness-epidemic

Be First to Comment