In the course “Dynamics of Individual Differences“, students write a blog post on a topic of their interest. Lotte van Aperen shared her blog post with us, enjoy the read!

As a parent, you might not like thinking about the sexuality of your little angel. It is however, an essential part of your child’s development that you might influence substantially with your parenting, for the better or for the worse. That’s why it is essential to look at how different ways of parenting influence the sexual health of the child. In this blogpost, we will explore the relationship between parenting and sexual health, and learn how to make sure that our children can enjoy rather than regret their sexuality.

“Sexual health”, what is it?…

Let’s first establish what we mean by “sexual health”. The definition by the World Health Organization includes of course the absence of disease, so remaining physically healthy, not contracting any sexual ly transmitted diseases (STD’s) for example. The proper use of birth control is also part of sexual health, which can for example be impaired when access to birth-control is restricted. This is a very old and limited definition of sexual health. Nowadays it also includes the possibility for safely having pleasurable experiences with sex, free of force and discrimination (World Health Organization: WHO, 2019).

Why care?

Considering this definition of sexual health, the increase in the number of STD’s and the decrease in use of contraception is a worrisome trend (NOS, 2024). On top of that, did you know that in the Netherlands it is estimated that 1 in 10 people have experienced sexual violence in the form of physical force or intimidation? This sexual violence also occurs more often against women, homosexual and bisexual people and those who do not consider themselves either male or female, which suggests that discrimination is indeed damaging their sexual health (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, 2024).

What can I do?

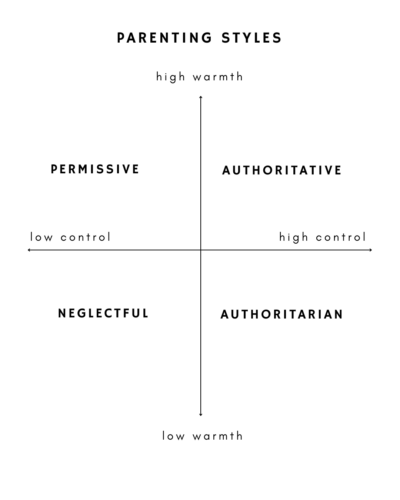

So how could you as a parent try to make sure that the sexual health of your child is as good as possible? You might think about having “the talk” with your children about the birds and the bees, but actually how you “parent” on a day-to-day basis already has profound implications for your child’s sexual development. Most research on the so called “parenting-styles” focuses on two dimensions of parenting (Estlein, 2016).

One of these dimensions is warmth, it refers to the amount of affection you show to your child and how responsive you are to their needs. If your little son comes running to you because his finger got stuck in the cabinet door and you respond with something along these lines: “Oh, did it hurt, I’m so sorry, do you want a kiss? All better?” it would be high warmth. On the other hand, if you response looks more like: “Oh it’s nothing, now, big boys don’t cry.”, or there would be no response at all, it would be low in warmth.

The other dimension is control, or how many rules you have and how reasonable they are. It refers to how demanding you are of your child. Say you have a teenager who wants to go to a party. Parents very low on control might not even ask of their teenager to tell them about the party and would not wonder why their child is not home. You can also be high in control and set very strict conditions under which you let them go or you could not let them go at all. Or you might fall somewhere in between by maybe setting a curfew and having them travel only together with friends. In the picture you can see how these two dimensions create the four classic parenting styles first created by Baumrind and later built on by Maccoby and Martin (1983).

What does a “parenting style” have to do with sex?

What’s interesting about these parenting styles is that research shows that using certain styles likely leads to better sexual health outcomes for the children. De Graaf et al. (2010) found that adolescents whose parents are high in warmth generally have their first sexual interaction at a later age, are more likely to use condoms, have more sex-positivity and are more competent in sexual interactions.

De Graaf et al. (2010) also looked at control, which is a slightly more complicated issue. Both too much and too little control seem to lead to worse outcomes for sexual development. Children whose parents use an appropriate amount of control start having sex at a later age, are more likely to use condoms and have more pleasurable sexual experiences. When parents use either to little or too much control however, their children start having sex earlier, are less likely to use condoms and have less pleasurable experiences.

Girls who experienced any parenting style other than a combination of high warmth and, appropriate control, report having had more unwanted sexual contact and they feel more guilty about their first sexual experience if they have overly strict fathers. Adolescents with a mother who is high in control and low on warmth experience more difficulty with sexual communication (de Graaf et al, 2010).

Determining exactly what an appropriate amount of control is, is very difficult for two reasons: First, there are likely vast differences between children, and how much control is appropriate for them. Second, the previous research is presented as if parenting style necessarily influences the child but of course, parents likely also adapt their parenting style according to their children. There has been research that has shown that the parenting comes before the child’s sexual behavior (de Graaf et al. 2010), but since we cannot practically or ethically manipulate parenting-style throughout an entire childhood, we cannot confidently say there is not some other factor causing both the parenting-style and the child’s behavior. Still, in the majority of cases, the children whose parents are warm and moderate on control, do best.

Good control is a balance between assertive but fair,

but also depends on the child.

But there’s more to it than that

Of course there are other important factors when it comes to raising a sexually healthy individual. For example, we cannot pretend that exploring sexuality is the same for young girls as for young boys. Another study by Kincaid et al. (2012) looked at how all of these effects might differ between adolescent sons or daughters. In general it seems that for girls warmth is more important and for boys control is more important. One might want to conclude from this that we should be tougher on our sons and more loving to our daughters but this is not the case. Being both high on warmth and appropriate on control is better for both girls and boys, but the effect of control is stronger for boys and the effect of warmth is stronger for girls. Exactly why this is the case we don’t know. The authors propose that these differences are due to biology and genetics but the evidence that supports this is difficult to find.

Treating boys and girls differently already starts essentially from birth on (Stacey, 2021) by picking gender-conforming toys and suggesting and condoning gender-conforming hobbies for example. Therefore, it might seem more logical to look for explanations on a societal level.

When we don’t know where gender differences come from,

We have the tendency to conclude that it is biological without evidence.

We likely hold a large number of beliefs about how women differ from men that are based on stereotypes. An example of such a gender-stereotype within sexology would be the false idea than men have a higher “sex-drive” then women. This is not true, yet many people believe it (Laan & van Lunsen, 2023).

Green (2005) shows how gendered stereotypes lead to completely different implications for sexuality for girls and boys. She also shows how the presence of these stereotypes can be incredibly harmful for the sexual development of both girls and boys, with a strong patriarchal macho culture being related to homophobia, slut-shaming and rape condoning. So it is clear that the consequences of this difference in treatment is not always limited to guiding girls towards ballet and boys towards football.

But I don’t treat my son differently than my daughter

Parents guide their children according to their gender in different ways, including ways you are most likely not aware of (Mesman & Groeneveld, 2017). Research on gender differences in parenting styles suggests that parents do tend to use different parenting styles for their sons compared to their daughters. This difference is especially present in fathers, but both mothers and fathers tend to be less warm with their sons (Vyas et al., 2016).

When it comes to parenting specifically about sexuality however, we might see a slightly different view. In the article by Bangpan and Operario (2012) it is described how women feel that parents have a double standard in the expression of sexuality. That of a daughter is prohibited, whereas a sons expression of sexuality was accepted. In general women perceive their sexuality as being repressed. This would suggest that parents actually are in general higher on control for their daughters than their sons regarding their sexuality. More research on whether parents perceive this as well and if more objective measures also show this is currently lacking.

Even if it is subconsciously,

Parents treat their sons and daughters differently.

We should on the other hand not expect parents to treat all of their children exactly the same, nor is it necessary or always beneficial. Children differ, not only based on gender, and require different kinds of guidance. What we should keep evaluating however, is whether these differences in treatment are actually based on what is best for the child.

What now?

So what can we conclude from all of this? Let’s have a quick summary. Firstly, general parenting styles have an impact on the sexual health of adolescents, so that high on warmth and appropriate on control will predict the best outcomes. Second, parents treat their sons and daughters differently, possibly in ways they should not, since there are no biological reasons found for these differences and stereotyping could be harmful. As a takeaway message: when you raise a son or a daughter or both, show them affection, be warm, set appropriate rules, and be aware that you might have the tendency to be less warm with your son. Also be aware that you might hold different standards for your son and daughter when it comes to sexuality, and ask yourself if this is really appropriate. If you doubt about what concrete appropriate parenting practices are, this blogpost by Dewar (2024) can give you some more concrete information: https://parentingscience.com/authoritative-parenting-style/.

Some disclaimers

1) Research in this field is unfortunately still largely heteronormative, that is, it mainly looks at heterosexual and cisgender people. We don’t know what these effects look like for queer parents and likely more relevant, queer adolescents. Just like we could not assume that the sexual development of boys and girls is the same, it would be strange to assume that the development of homosexual adolescents is the same as that of heterosexual adolescents. For example, contraceptive methods are not as relevant for them, whereas dealing with stereotype and possibly discrimination is.

2) What research often calls “sexual risk behavior” can be debated. Whether sexual behavior is risky often depends on the situation (obviously, not using a condom is not risky if you know for sure you both have no STD’s and if you are trying to get pregnant or are infertile for example.). Other relevant factors that might be risky, like improper hygiene, are almost never considered.

Author: Lotte van Aperen

References

Bangpan, M., & Operario, D. (2012). Understanding the role of family on sexual-risk decisions of young women: A systematic review. AIDS Care, 24(9), 1163–1172. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2012.699667

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. (2024, 25 november). Ruim 1,7 miljoen slachtoffers van seksueel grensoverschrijdend gedrag. Centraal Bureau Voor de Statistiek. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2024/48/ruim-1-7-miljoen-slachtoffers-van-seksueelgrensoverschrijdend-gedrag

De Graaf, H., Vanwesenbeeck, I., Woertman, L., & Meeus, W. (2010). Parenting and Adolescents’ Sexual Development in Western Societies. European Psychologist, 16(1), 21– 31. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000031

Dewar, G. (2024, 25 april). The authoritative parenting style: An evidence-based guide. PARENTING SCIENCE. https://parentingscience.com/authoritative-parenting-style/

Estlein, R. (2016). Parenting styles. Encyclopedia Of Family Studies, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119085621.wbefs030

Green, L. (2005). Theorizing Sexuality, Sexual Abuse and Residential Children’s Homes: Adding Gender to the Equation. The British Journal Of Social Work, 35(4), 453–481. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bch191

Kincaid, C., Jones, D. J., Sterrett, E., & McKee, L. (2012). A review of parenting and adolescent sexual behavior: The moderating role of gender. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(3), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.002

Laan, E., & Lunsen, R., van. (2023). De Waarheid Over Seks (1ste editie). de Arbeidspers. 10

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the Context of the Family: Parent–Child Interaction. Handbook of Child Psychology, 4.

Mesman, J., & Groeneveld, M. G. (2017). Gendered Parenting in Early Childhood: Subtle But Unmistakable if You Know Where to Look. Child Development Perspectives, 12(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12250

NOS. (2024, 7 maart). Europees gezondheidsinstituut: steeds meer mensen met een soa in Europa. https://nos.nl/artikel/2511849-europees-gezondheidsinstituut-steeds-meermensen-met-een-soa-in-europa

Stacey, L. (2021). The family as gender and sexuality factory: A review of the literature and future directions. Sociology Compass, 15(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12864

Vyas, K., Bano, S., & Islamia, J. M. (2016). Child’s gender and parenting styles. Delhi Psychiatry J, 19(2), 289-93.

World Health Organization: WHO. (2019, August 27). Sexual health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/sexual-health#tab=tab_1

Images from pinterest:

https://pin.it/4jKbpTVyf

https://pin.it/6ynlN0p02

https://pin.it/7fX1bMXVS

https://pin.it/5wHg8PVud

Figure of parenting styles: Created by Zeynep Ayhan

Be First to Comment